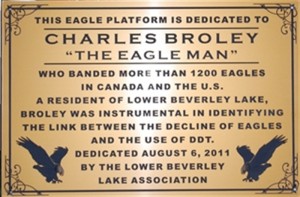

Eagle Platform, Location: Blue Heron Point

Eagle Platform Dedication

On August 6, 2011 the Lower Beverley Lake Association dedicated its first eagle platform to the memory of Charles Broley. It is only fitting that we encourage eagles to nest where the Eagle Man once soared! The Eagle platform is located near Blue Heron Point(#26 in the Self-guided tour brochure)

Broley, Charles (Lavelle). Born in Gorrie, near Goderich, Ontario, on December 7, 1879; He died in Delta Ontario, May 4, 1959. Naturalist, ornithologist, bander, banker

FAMILY AND EDUCATION

Broley was the son of a strict Methodist minister. His family moved several times to various villages and towns in general vicinity of Elora, Ontario, finally settling in Islet Rock in 1886. He attended public schools with his brother and two sisters but did not undertake further formal education. Charles married his first wife, Ruby Stevens, about 1908. She died in 1921. His second wife was Myrtle McCarthy. They were married in 1923. She died 1958. Charles and Myrtle had one daughter, Jeanne Broley Patric.

POSITIONS

- Manager, Merchant Bank, Delta, Ontario 1905-1918.

- Manager, Croydon Avenue branch, Bank of Montreal, Manitoba 1918-1938.

- Secretary Ornithological Section, Natural History of Manitoba, (NHSM) 1924-1925, 1928-1929; chairman 1925-1928, 1929-1930, [vice president, NHSM, 1931-1934.]

- Appointed to Wildlife Committee, Florida Audubon Society, shortly before his death, 1959.

CAREER

Professionally, Broley was a banker, first in southern Ontario, then in Winnipeg, Manitoba. His interest in nature, was apparently stirred at his cabin in Ontario, but did not develop strongly until after the death of his first wife. In Manitoba, he became very active and contributed regularly to A. G. Lawrence’s bird column, “Chickadee Notes,” in which Broley reported a number of significant observations. He applied his thorough, careful banker’s discipline to observing and reporting and quickly became known for his reliability. These traits, combined with his good humor and active nature, led to his participation and popularity in the Natural History Society of Manitoba, with the enthusiastic support of his second wife, Myrtly. Among his many observations there was the mysterious death of a large number of Franklin’s gulls, attributed by him to their eating poisoned grasshoppers.

Broley retired from the bank in 1938 at the age of fifty-eight, and after a brief period of European travel, he and Myrtle started the annual pattern of wintering in Florida and summering at the cabin in Delta, Ontario. In Florida, he started an extensive program of banding bald eagles, of which only 166 had been banded previously. He soon became adept at climbing to nests, eventually banding over 1200 eagles, primarily in Florida, with about 100 also in Ontario. Recoveries showed that “resident” eagles of Florida underwent extensive wanderings to the north after nesting and completely revised previous thinking on the life history of the species. These significant results earned him an elective membership in the American Ornithologists’ Union (1959) but more significantly his popular lectures on subject brought much publicity and popularity to the eagles, and he became a popular subject of writers, notably in J. J. Hickey’s classic bird-watching guide and an Audubon article by R. T. Peterson. This work and his earlier observations in Manitoba also resulted in a honorary life membership in the Natural History Society of Manitoba in 1944.

Broley’s careful records at large numbers of nests took on new significance in 1947, when hatching success suddenly declined. The coincidence of this decline with the start of DDT spraying in the area was not unnoticed, and after carefully considering other possibilities, Broley concluded that DDT was the culprit, and his several articles and lectures on the topic were among the early warnings of the dangers of chemical pollution in the environment. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring effectively used Broley’s data in combination with others to sound this warning.

Manitoba observations were published in Lawrence’s column. Broley wrote about ten papers on his eagle work, and Myrtle published popular book on his work (1952)

MAJOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Broley’s studies elucidated many details of nesting and post-nesting biology of Bald Eagles, and his lectures helped popularize the eagle. His investigations were among the first to implicate DDT in raptor declines and thus pesticides as environmental threats.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bodsworth, F. “How to Catch an Eagle.” Maclean’s Magazine 65, 3 (1952).

Broley, C. L. “The Eagle and Me.” Canadian Banker 60 (1953).

Broley, M. J. Eagle Man (1952).

Gerrard, J. Charles Broley: An Extraordinary Naturalist (1983).

Hickey, J. J. A Guide to Bird Watching (1943).

Mager, D “Charles Broley in Florida.” In J. M. Gerrard and T. M. Ingram, eds., The Bald Eagle in Canada (1985).

Mason, C. R. Auk 77 (1960) (obit.).

McKeating, G. “Charles Broley: Eagles The and Now in Southern Ontario.” J. M. Gerrard and T. M. Ingram, eds., The Bald Eagle in Canada (1985).

McMaster, A. “Charles Broley in Manitoba.” In J. M. Gerrard and T. M. Ingram, eds., The Bald Eagle in Canada (1985).

McNicholl, M. K. The Canadian Encyclopedia (1985, 1988).

Peterson, R. T. “Eagle Man.” Audubon 50 (1948).

UNPUBLISHED SOURCES

Eagle records and films at Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Martin K. McNicholl.

from: CHARLES BROLEY: AN EXTRAORDINARY

NATURALIST.

Genard, Jon.

Jon Gerrard, a medical doctor in Manitoba, developed an interest in bald eagles. As a result of this interest, he became interested in the life of Charles Broley and had the opportunity to meet Jeanne, Charles’s daughter, and visit the site of the family cottage at Delta, Ontario. This, along with the writings he had perused of Charles Broley’s pioneer work in bird watching and the banding of bald eagles, lead Gerrard to write a paper for a conference on bald eagles that was being held in Winnipeg.

Unfortunately, there are several gaps in the life of Charles Broley that Gerrard could only surmise about, and these he has acknowledged. Charles Broley was raised in Elora, Ontario. He became a banker, moved to Delta, where he met and married his first wife, Ruby, and built the family cottage on an island. Unfortunately, he lost Ruby to tuberculosis. He moved to Manitoba, where he met his second wife, Myrtle. At this time in his life he became an avid bird watcher, as did Myrtle. He became highly respected for his knowledge of birds and upon his retirement, at the age of sixty, began climbing one hundred foot high trees to band eagles. After several years of banding, Charles began to notice a decline in successful nestings of the eagles and was responsible for raising enough concern that political action brought about a ban on DDT.

Shortly after Myrtle’s death Charles died trying to extinguish a grass fire that burnt his cottage. By his personal efforts Charles had greatly encouraged an interest in bird sanctuaries and bird conservation in general. Avid hunters became avid bird watchers and photograhers. This is a story that needed telling and it would be a worthwhile addition to the bird section of all libraries.

History of the Building

Elora Public School, circa 1912

Elora Public School, circa 1912

The Elora School has stood for 145 years, serving students of the Village of Elora.

Now a designated heritage building, the structure is a product of 80 years of construction and renovation undertaken to meet the needs of growing student enrolment while working with the constraints of tight budgets. The resulting disarray of styles and forms has led some to view the school as an inefficient monstrosity, while others (like Elora Centre for the Arts) see it as a charming, historic treasure.

The earliest part of the building is the first story on the south-east corner, constructed in 1856 as the village’s girls’ school. In 1866, a new boys’ school was constructed to the north and connected to the girls’ school. By 1871, boys and girls education was integrated. By 1874, the north wing was added and the former girls’ school became the high school.

Over the years, improvements included central heating (1895 using four furnaces), electric lights and bathrooms (1927) and central steam heating (1935). The final addition was the three-story structure built on the south-west corner in 1939 to serve an enlarged high school enrolment. This is believed to be the last stone building built in Elora.With the construction of a new high school in 1959, the building reverted to a public school. The high school was converted to a senior public school in 1970, and the original building became a Junior Public School.

The school was closed in 1996. At that time, the original girls’ school was probably the oldest active school building in the province, while the 1939 addition was the last three-story structure still in use in the country.

Many well-known citizens attended the Elora school.Those who achieved respect outside the community include: John Connon, local historian and photographer, who invented the panoramic camera; John Drew, lawyer, whose son George Drew became Premier of Ontario, Charles Kirk Clarke, psychiatrist, after whom the Clarke Institute of Psychiatry is named, and Marion Roberts,who married Fredrick Banting, discoverer of insulin. Charles Broley,a student of David Boyle, was an avid birder and was one of the first to identify the effects of DDT on birds, work that Rachel Carson used in her groundbreaking book Silent Spring. One of the greatest contributors to the school was David Boyle, who served as Principal from 1871 to 1881. A key figure in Elora’s 19th century intellectual life, Boyle enriched Elora with his pioneering work in geology and archeology.

David Boyle & The School

One of the greatest contributors to the school was David Boyle, who served as principal from 1871 to 1881. A key figure in Elora’ s 19th century intellectual life, Boyle enriched Elora with his pioneering work in geology and archeology. Though he possessed no formal training as a teacher, Boyle was obsessed with theories of education. He rejected traditional teaching methods, instead developing a child-centred philosophy that encouraged reasoning and understanding, fostered by the student’s own natural curiosity about the things around them. Boyle believed that girls were fully capable of understanding scientific subjects and solving mathematical problems. During Boyle’s tenure, six new rooms were added to the school- one of which Boyle set up as a museum, containing archeological specimens, minerals, curiosities, and other artifacts that he used as teaching aids. Interestingly, when Boyle moved to Toronto, he brought his collection of native artifacts and relics that he had collected in the Elora area, eventually placing them in the Ontario Provincial Museum. In 1933 this collection was transferred to the David Boyle room at the Royal Ontario Museum.

as principal from 1871 to 1881. A key figure in Elora’ s 19th century intellectual life, Boyle enriched Elora with his pioneering work in geology and archeology. Though he possessed no formal training as a teacher, Boyle was obsessed with theories of education. He rejected traditional teaching methods, instead developing a child-centred philosophy that encouraged reasoning and understanding, fostered by the student’s own natural curiosity about the things around them. Boyle believed that girls were fully capable of understanding scientific subjects and solving mathematical problems. During Boyle’s tenure, six new rooms were added to the school- one of which Boyle set up as a museum, containing archeological specimens, minerals, curiosities, and other artifacts that he used as teaching aids. Interestingly, when Boyle moved to Toronto, he brought his collection of native artifacts and relics that he had collected in the Elora area, eventually placing them in the Ontario Provincial Museum. In 1933 this collection was transferred to the David Boyle room at the Royal Ontario Museum.

Champion Eagle Bander Charles L. Broley

About the champion eagle bander Charles L. Broley, history and biography of the man who tagged bald eagles.

The Champion Eagle Bander. Charles L. Broley, the “eagle man,” made a major contribution to man’s understanding of the bald eagle. By profession, Broley was a bank manager in Manitoba. But when he retired in 1938, and sought a hobby to occupy his time, he turned to birdwatching. Before long, his interest was focused on eagles, and he spent much of his time scaling trees in search of them.

He would swing, spiderlike, on a web of fragile ropes, 100′ above the earth, until he could secure a death grip on a jungle of sticks and heave himself into a nest of protesting–and sometimes threatening–birds.”

Broley became concerned with the bald eagle after learning how land developers and irresponsible gunners had been driving them from their nesting trees. “The Florida eagles, prior to 1939, were also giving up a large share of their annual egg production to oologists, that band of incurable kleptomaniacs who took thousands of eggs from the nests of wild birds and kept them in carefully labeled storage cases.”

There was also the unsolved mystery of why a sizable segment of the Florida eagle population would vanish from the State during the summer. No one knew where it went, or why it returned each fall.

A professional conservationist, Richard H. Pough, issued Broley 4 eagle bands and a banding permit. “Try banding some nestlings,” Pough suggested. And then he quickly added, “Find a boy to do your climbing.” Shinnying up trees was not an advisable pastime for retired bankers so far as Pough was concerned.

Traveling south to Tampa, Broley decided to do his own climbing, and he set out to design his own climbing equipment. “Next he began building a rope ladder with 2 long pieces of rope, between which he fitted 12″ sections of wood as steps.”

But Broley had severe problems securing this ladder in nesting trees. He used weights and pulleys for a while. “Later refinements of this system included a slingshot, which Broley handled with uncanny accuracy, and a fisherman’s large casting reel to keep the line from tangling.”

Once the ladder was in place and Broley had climbed to the top, he encountered his most serious problem. “No man is welcomed to the home of an eagle.” Nevertheless, Broley would actually climb into the nest, grab the reluctant bird’s left wing, hold it down with his knee, and then grope for its left foot to attach the aluminum band.

“The 1st year Broley banded 44 eagles, more than had ever been banded before in all of Florida. Broley began to get occasional returns from his banded eagles, and from surprisingly distant points. More than 1/3 of the recovered bands were taken from eagles 1,000 mi. or more up the eastern seaboard from their home nests.”

Broley continued banding eagles for 12 years. He did all his banding in Florida, and spent his summers in Ontario where he “trained” for the work ahead of him. “When I could chin myself 18 times without pausing, I figured I was ready to climb again,” he said.

Broley never fell from a tree nor was he ever injured by an eagle. During his remarkable retirement career, “he banded more than 1,200 eagles. His eagle work ended with the 1958 season. He had searched as diligently as ever along the same 100 mi. of coast where a short time ago he had banded as many as 150 eagles a year. But at the end of the season he had located only one young bald eagle on which to place a band.”

In the spring of 1959, Broley died, “not by falling 100′ from the top of a longleaf pine tree, but while fighting a brush fire near his home in Canada.”